- News

- Reviews

- Bikes

- Accessories

- Accessories - misc

- Computer mounts

- Bags

- Bar ends

- Bike bags & cases

- Bottle cages

- Bottles

- Cameras

- Car racks

- Child seats

- Computers

- Glasses

- GPS units

- Helmets

- Lights - front

- Lights - rear

- Lights - sets

- Locks

- Mirrors

- Mudguards

- Racks

- Pumps & CO2 inflators

- Puncture kits

- Reflectives

- Smart watches

- Stands and racks

- Trailers

- Clothing

- Components

- Bar tape & grips

- Bottom brackets

- Brake & gear cables

- Brake & STI levers

- Brake pads & spares

- Brakes

- Cassettes & freewheels

- Chains

- Chainsets & chainrings

- Derailleurs - front

- Derailleurs - rear

- Forks

- Gear levers & shifters

- Groupsets

- Handlebars & extensions

- Headsets

- Hubs

- Inner tubes

- Pedals

- Quick releases & skewers

- Saddles

- Seatposts

- Stems

- Wheels

- Tyres

- Health, fitness and nutrition

- Tools and workshop

- Miscellaneous

- Cross country mountain bikes

- Tubeless valves

- Buyers Guides

- Features

- Forum

- Recommends

- Podcast

OPINION

Paper And String

My first ever bike adventure, to somewhere less than ten miles away, was a list of road names written on a strip of paper Sellotaped into a loop round my handlebars by my stem, a bit like an analogue Sat Nav, about thirty years before Sat Navs existed. It rattled around and kept slipping down to the right-hand brake lever, but its simple directions got me to where I wanted to be via the unfamiliar but empty roads of rolling suburbia. And by reading it backwards it got me home again.

Nothing much has changed. Despite the current proliferation of digital tools I still prefer my rides to involve bits of paper.

Way back when in what are now known as my formative years GPS devices didn’t even exist and bike computers weren’t in any way common, unless you called the car-like speedo that ran off a wheel that rubbed on the front tyre a kind of computer. How I desired the overly large multi-coloured plastic clunkiness of one of those, that and the milometer that mounted discreetly on the front forks which counted the clicks of the passing tab on the spokes, available for 27”or 700c wheels. My father had one on his Dawes 5-speed - a sign of maturity and knowing. I rode circles of the lawn to cover a mile just to watch the little number click forward one. The endless circles of the lawn with a growing feeling of fear that my Dad would notice the change of numbers. He wrote things down did Dad.

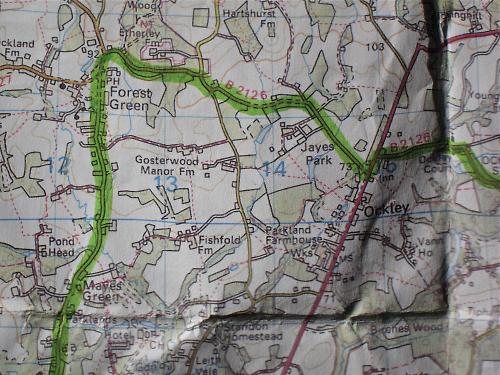

As my world expanded further from that pioneering trip through the houses I would spend hours on my tummy on the front-room floor, pink Ordnance Survey map laid out flat in front of me, possibly a cup of tea and some biscuits in the vicinity, legs pedaling the air, index finger worn smooth from tracing out lines on the map, forming a route that used as many of the traffic thin yellow roads as possible. Then the Special Bit Of String from the second drawer down that held all the Useful Things would be fetched and lain out over the proposed route on the map. The length was marked and then measured out against the distance scale along the bottom of the map, anything over four lengths of the scale was a good ride back then. My entire cycling world was boundaried by the margins of that map, fire-breathing griffins and angry spouting sea monsters lurked off the edges, it would be some time before I tentatively made excursions onto another piece of paper and it was like exploring the New World.

About then proper bike computers arrived and knowing the ride distance became instant, making the Special Bit Of String instantly obsolete and slowly it sank to the bottom of the second drawer down, buried under more Useful Things. But the maps still came out to plan days out, although less and less often as routes slotted into memory and a vast database of rides could instantly be called upon to suit distance and mood.

Now there are vast chunks of the world collected in folded bits of paper that fill a large part of the bookshelf. UK ones up there, foreign ones in box files by country down there. When going somewhere new a fresh corresponding map has to be bought. It’s the law. Nothing compares to opening up the crisp folds of an unfamiliar land and spreading out all the imagined possibilities in front of you. Looking for any remembered names, making a note of the crowding of contours, tracing with the index finger worn smooth the tempting wiggle of roads and being suddenly aware of the clusters of black arrows. A mix of longing, excitement and fear.

Over the years I have developed a weird exploratory quirk; a consequence of spending the majority of my life butted against a coast. My local map is 50% useless, everything south of my house is a no-go area for bikes, they don’t do so well in the bottom half of blue. My rides mostly involve going up, and not just because I live at sea level. Such is the habit of a lifetime looking at the top half of the map it takes a massive mental wrench when opening a new map to drag the eyes southwards and see what lurks there, where land and hills don’t ever usually exist.

Those new maps slowly become creases of paper that carry the tattered corners, ripped seams, faded sections and muddy smears of fun, effort and memories. Once more to be unfurled onto the front room carpet, legs flailing the air, pedaling the route again, and this time to be read like a book, recounting stories of the smiles and tears traced out along roads and byways.

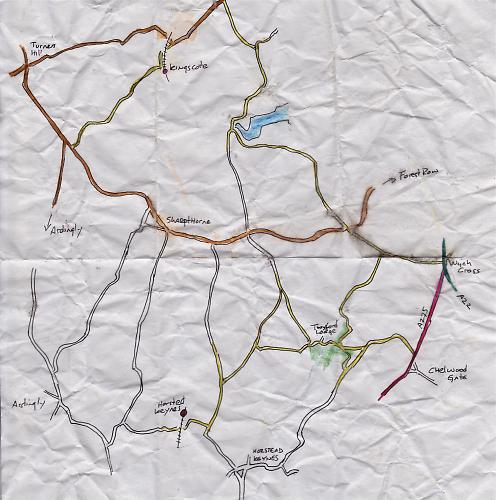

Alongside the broad ridge of thin pink and yellow and orange spines is a pile of paper. Folded, creased, torn and stained scraps with lines of roads and names drawn on with fine pen. Sketched to fill gaps in any route knowledge, joining that known bit to that known bit, extending a well known loop a little bit further, exploring outside of the usual jurisdiction, any reason that just a small section of map is needed rather than the whole sheet. The relevant area traced off onto an easily pocketable tear of paper, or maybe if I’m feeling posh a photocopy and a highlighter pen, to be pulled out at that junction that leads away from the acquainted, to help with the leap into the unknown.

But the common habit now is to look at a screen. All we do now is look at screens, for work, for fun, for friends, for talking, for interacting, for riding bikes. The luscious language of the landscape has been reduced to binary, a list of numbers, lines, stats and graphs. Granted, computers have made things easier in that you can plan a route in the comfort of sitting down, endlessly fiddle with the route so that the mileage fits and then download it to your box of handlebar tricks that will tell you where to go. Or let someone else do the hard work and simply Plug and Play. And then you will instantly know how far you’ve been, at what speed, where the steepest hills were and who you beat along the way. And you can immediately and urgently tell all this to anyone else that just so happens to be looking at a screen at the time.

All very impressive and requisite for showing off but you will never get a feel for the land from a 2” screen. It won’t be able to feed an imagination by describing the woods and forests and lakes and rivers and villages you’ll pass. Why that road does that wiggle, that bend. Computers follow a line, a map adds colour, depth, meaning and history. In this ubiquitous oppressive digital world I still like to escape with my finger, disappear into the narrative of a map. And you can buy an awful lot of maps for the same price as a handlebar mounted toy.

Maps tell stories - electronic devices just beep.

Jo Burt has spent the majority of his life riding bikes, drawing bikes and writing about bikes. When he's not scribbling pictures for the whole gamut of cycling media he writes words about them for road.cc and when he's not doing either of those he's pedaling. Then in whatever spare minutes there are in between he's agonizing over getting his socks, cycling cap and bar-tape to coordinate just so. And is quietly disappointed that yours don't He rides and races road bikes a bit, cyclo-cross bikes a lot and mountainbikes a fair bit too. Would rather be up a mountain.

More Opinion

Latest Comments

- Geoff H 7 min 29 sec ago

For the home mechanic, how often does the torque wrench need to be reclibrated?

- eburtthebike 8 min 24 sec ago

The grip that the right wing reactionaries have on the gullible public is frightening, and this is just a microcosm of that influence, with so many...

- chrisonabike 10 min 33 sec ago

I know a good book about that!

- chrisonabike 18 min 24 sec ago

But ... and I know this is beyond the DfT, but announced funding was then cut (even that which didn't turn out to be some political sleight of hand...

- froze 59 min 1 sec ago

I bought a Topeak Joe Blow Sport III Pump about 9 months ago, quite frankly, I was not impressed with it. The base has too much flex it in it, the...

- froze 1 hour 12 min ago

Ride single file, stay close to the curb? Where I live, I get people screaming at cyclists telling them they don't belong on the road, I was...

- james-o 1 hour 21 min ago

The worst thing about all this is learning that Bon Scott's family tried to make sunglasses with his name on.

- KDee 1 hour 25 min ago

There's a whiff of Martin73 about that post from whosatthewheel.

- mdavidford 2 hours 51 min ago

I assumed that a commuter road was like the Room of Requirement - it travels to wherever people need to drive on it.

- Simon14 5 hours 1 min ago

Anyone 6'3 here? Torn on sizing. I ride size 58 in Specialized and Cannondale, Large in Giant, Large in Canyon, saddle height 82cm. I really like...

Add new comment

37 comments

This reminds me very strongly of my childhood. I grew up in Chester (Landranger 117!), and any trips into North Wales had to be by memory after you passed the appropriately named Hope, as I had no map of that area at all. In fact I still haven't, but can still remember the routes when I return, around 30 years later.

The string and scale method has been deployed for bike routes throughout the country and mountaineering trips to Scotland and the Dolomites.

"When going somewhere new a fresh corresponding map has to be bought. It’s the law. Nothing compares to opening up the crisp folds of an unfamiliar land and spreading out all the imagined possibilities in front of you. Looking for any remembered names, making a note of the crowding of contours, tracing with the index finger worn smooth the tempting wiggle of roads and being suddenly aware of the clusters of black arrows. A mix of longing, excitement and fear."

Exactly. It is the law. Maps are like good books - they do indeed tell a story, initially of the land you are about to cross and after of epic rides or roads to avoid.

I have boxes full of maps and the important/most used ones on the shelf. My wife says I have too many, I still think there are significant gaps in my collection.

Roger that! My world, like most, is packed with screens and numbers. Instructions and orders. The world sees ours lives on twitter and Facebook. Sod taking on more exposure and having to keep up appearances.

A map is a world of possibility. I decide. I can change my mind. Tit about. Explore. Alone. Or with company. My world.

My teenage map reading also means I can...read a map. Which also means when the iphone is dead or the GPS doesn't work, I can find my way home. I have a very visual memory of the roads I ride and their place together...I tend to know whether I'm heading north and what direction to turn even without sun. It's got me out of some nasty fixes in foreign cities and unlit roads. That was trained, from having tonne aware of my surroundings.

When I gave up racing I chucked all my computers. I live to look around and absorb. Memorise the sights. Despite finding numbers fascinating and having a sports science degree, I refuse Strava like a Neanderthal.

I'm free, to do what I want, any old tiiiiime.

Yes!

True (says an ardent map lover).

There is satisfaction to be had in gaining an understanding where places are in relation to each other, how to get there and what kind of terrain and type of road/track/path you can choose in between, all before you have left the house.

You can rip the relevant page from a Road Atlas (£1.99 at The Works) and pop it in an A4 polypocket. Fits in a jersey pocket when folded in half.

Hah, this is exactly what I did when I did LEJoG over a decade ago. As a poor student I could barely afford spare inner tubes, let alone a bike computer, so we plotted the route on a couple of those and tore the pages out.

I took great satisfaction in throwing away each page as we crossed over onto the next on our epic journey across the country. I still have the last page somewhere, a tatty copy of the north coast of Scotland on the cheapest, thinnest paper you can imagine. But it worked absolutely fine for over a thousand miles on completely unfamiliar roads, a great testament indeed.

nice.................

Pages