- News

- Reviews

- Bikes

- Components

- Bar tape & grips

- Bottom brackets

- Brake & gear cables

- Brake & STI levers

- Brake pads & spares

- Brakes

- Cassettes & freewheels

- Chains

- Chainsets & chainrings

- Derailleurs - front

- Derailleurs - rear

- Forks

- Gear levers & shifters

- Groupsets

- Handlebars & extensions

- Headsets

- Hubs

- Inner tubes

- Pedals

- Quick releases & skewers

- Saddles

- Seatposts

- Stems

- Wheels

- Tyres

- Tubeless valves

- Accessories

- Accessories - misc

- Computer mounts

- Bags

- Bar ends

- Bike bags & cases

- Bottle cages

- Bottles

- Cameras

- Car racks

- Child seats

- Computers

- Glasses

- GPS units

- Helmets

- Lights - front

- Lights - rear

- Lights - sets

- Locks

- Mirrors

- Mudguards

- Racks

- Pumps & CO2 inflators

- Puncture kits

- Reflectives

- Smart watches

- Stands and racks

- Trailers

- Clothing

- Health, fitness and nutrition

- Tools and workshop

- Miscellaneous

- Buyers Guides

- Features

- Forum

- Recommends

- Podcast

feature

Fools suffer gladly

In the lexicon of cycling shorthand Belgium is Suffering. It’s the Spring Classics, it is cobbles, it’s grey grit and mud-freckled faces grimacing into a drizzly headwind, it is pain, it is Merckx dishing the pain out. Belgium is where the Hard Men live, it is for the tough, it’s where you go to play at being rugged, to willingly get beaten to bits over the pavé, it’s where to Suffer. Applying anything Belgian to your bike or yourself is to show just how much you like to Suffer. The simple addition of a black, yellow and red flag, or a lion rampant sable motif to socks and jerseys and bikes and coffee cups shows the world how gritty you are. It’s all about The Suffering.

I am in Belgium, and that is not suffering.

Walking into the main square in Ypres, or Ieper, or Wipers, it’s hard to believe that the whole place was a flat expanse of shelled rubble 100 years ago. The impressive Cloth Hall, Kasselrij and the ring of restaurants and shops look like they’ve been there forever instead of being less than a century old, all being rebuilt in the old style after the First World War. The large expanse of the Grote Markt is diversely full of school-parties regrouping before and after their Flanders Fields museum visit, a collection of World War Two army vehicles and a mass rally of Lotus cars during my short stay. The Market Square will be an impressive backdrop to the start of Stage 5 of this year’s Tour de France as it visits Ypres to commemorate the centenary of the start of the war to end wars.

Ypres played a crucial role in World War One, marked by three major battles in 1914, 1915 and 1917 that would destroy the town, the countryside and untold lives. Standing in the way of Germany’s sweep into Belgium and Northern France the Allies recaptured the strategically crucial city in the First Battle of Ypres in 1914 to leave it surrounded on three sides on the high ground that formed the boundary of the Ypres Salient. Much of what informs our popular perception of World War One happened in this area; trench warfare, cratered mud, Christmas truces, the first gas attacks, tunneling and wave upon wave of men sent to their end.

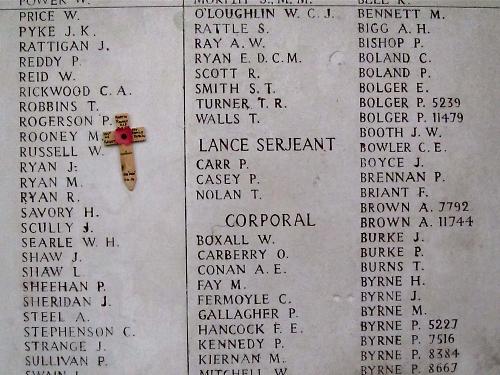

A minute’s walk up the road from the Grote Markt is the Menin Gate, on the eastern edge of the town it spans one of the main roads that Allied soldiers took to the front line and built to honour soldiers that have no known grave the memorial it’s decorated with nearly 55,000 names of the lost. The size and style of the monument almost suggests a triumphal arch but the absurd number of names carved into the walls overrules that. Browsing the rows upon rows upon rows of missing my eyes are brought to the line of names belonging to the Sussex Regiment, my home county. A few entries down I see my family surname. I don’t know if there is any relation, there certainly haven’t been any stories handed down, but still it brings a dryness to the throat and a speck of dust in the eye that needs rubbing out.

Every day since 1928 there has been a ceremony at the Menin Gate where the Last Post is played at 8pm for all these absent soldiers. The centenary of that war ensures that it’s a popular event this year and the vast space under the arch fills up with half an hour to go, the insipid drizzle probably encourages this. There is no sloppiness to proceedings that might have seeped in through frequency and it’s an elegant and sombre ceremony, only spoilt by the unrespectful in the audience with their constant bleeping, clicks and incandescence of iPhone, iPad and video screens all desperate to capture the experience without actually experiencing it.

This area of Belgium bordering on France is eclipsed somewhat by the romantic black and white punishing cycling ideal of central Flanders to the east, the sandy cyclo-cross Mecca of Koksijde in the north and the lumpy Ardennes in the south, home to Liège-Bastogne-Liège. The Heuvelland of West Flanders is a largely forgotten place, translated as “hilly country” it’s home to the Cinderella Spring classic of Gent-Wevelgem, a race that’s suffered until recently from being shoe-horned between the Ugly Sisters of the Tour of Flanders and Paris-Roubaix and not having much in the way of the romantic and exciting hardship of The Cobbles.

Guiding me around this unfamiliar corner is Dries Verclyte from Cycling In Flanders who could be Tom Boonen’s brother if you squint a bit after a few Leffes and he’s going to show me round the new HHR 40 route - a 110km ride that as the name might suggest, has 40 climbs in it. The start is in the small quiet village of Kemmel and astute cyclists might be able to deduce what the particular pudding in this Flandrian meal is going to be.

Of course, as it’s Belgium and to conform to our cyclist appeasing stereotype it’s been raining, and although that’s mostly stopped the sky remains a threatening grey and some of the farm lanes are still muddy and greasy. But those roads are empty and well surfaced, to the point that we’re denied going up one climb as it’s being completely re-tarmaced, we guess that this bit might be where the Tour comes through.

The HHR 40 ride squiggles and writhes around this pleasingly undulating and sparse part of Belgium, dips into France for a bit and each of the 40 hills en-route has a little named and numbered plaque at the bottom to let you know how many you’ve ticked off, or more importantly how many there are to go. With near on 1,500 metres of climbing it’s not the most altitude heavy ride, nor are the vast majority of the climbs going to raise a sweat, being either short sharp rises or long steady drags, but there are a few like the Katsberg to heavy the breath, and that one has a abbey brewery at the top for incentive. The frequency of the hills and the futility of going down a hill simply to climb back up it again nature of the ride means that your legs know that you’ve done 110kms, and if done at a pace higher than ‘chatty’ it would definitely hurt a bit.

Aside from the gentle relentlessness of the hills it’s easy to see why Belgium has the reputation for breeding hard men, for there is nowhere to hide. The wide and rolling landscape is frequently devoid of tree and hedge cover as the roads split wide fields allowing any breeze to thump its way into a cyclist’s chest. Even on this warmish and calmish day it doesn’t take much thought to realize how horrible this place could be in mid-winter, leaning unpleasantly into the weather.

I’ve been lent a Jaegher bike for the day, and not just any one, the owners own prototype model. He’s a bit taller than me so the bike is a little rangey for these little legs, but we make do, and if I wanted they would make one to fit me perfectly. Jaegher hand craft steel bikes in Ruiselede, Belgium and have been doing so since 1934, the Belgian bike brand you’ve never heard of. As was the way back then they made frames for other companies to put their stickers onto so sponsored riders such as Merckx, Kelly and Planckaert could ride something better than their manufacturer’s gas-pipe bikes and it’s only in recent years that the family name has made it onto the down-tube. No need to evoke some faux-Belgian heritage in the form of a lion on the seat-tube here then.

This Columbus steel prototype is unpainted, so it’s showing an artistic patina already, and with oversize tubing it’s designed to be stiff; standing up on the pedals and mashing the big ring as much as possible shows there’s very little in the way of yaw or sway, but when it comes to the cobbles that rigidity is readily apparent.

There’s plenty of opportunity to pause for refreshment along the way as the route wiggles through villages, we stop off at “In De Zon”, a cyclist owned restaurant it’s a popular place with regular punters and pedallers alike, especially on race day when the Gent-Wevelgem peloton goes straight past the front door. The place is tastefully decorated with cycling memorabilia and we’re allowed into the back where there’s a large garage of an Aladdin’s Cave of cycling bits and car-boot treasure.

The Kemmelberg is the sting in the tail of the HHR 40. Turning left just after the Cold War bunker, built as a command centre for NATO air defence, you’re onto the crucial climb of the Ghent-Wevelgem. Tackling the traditional ascent of the berg your legs have to deal with just under 400 metres of cobbles, they start off harsh through the trees, level off a tiny bit in the middle and then ramp up for giggles to a maximum gradient of 23% as the road swings round to the left past the church. At the summit you’re on the highest point in West Flanders, making it a crucial position in the First World War for lobbing shells onto the enemy, something the elegant angel of the Mémorial aux Soldats Français commemorates. But now it’s better known as a cycling battleground and the cobbles off the other side back to Kemmel are so steep and tricky that the race doesn’t go down here any more after one too many crashes in the peloton and it is actually quite scary, especially when you’re on Not Your Bike, and that bike’s a prototype, and the brakes are on the wrong way round. It focuses the mind.

Strong trappist beer and stew for supper. When in Belgium.

The following day’s ride is the Peace Route, a 45km loop around Ypres that takes in all the First World War sites, monuments and cemeteries that mark out the boundary of the Ypres Salient. It’s a casual ride on big heavy comfy town bikes, no lycra, no clipless pedals, no helmets and the perfect way to get connected with history. We clatter through the Menin Gate like so many before and head along the river that borders the town’s walls, the trim Ramparts Cemetery passes modestly on the right. We wheel left and left again to head south along the canal, Geert the guide is happy to be riding with someone that can pedal a bike as opposed to his usual groups that have the minimum of motor skills and fitness. He somehow manages to keep a cracking pace whilst delivering a constant stream of information, the perfect mix of facts and anecdote so it never becomes just a boring list of dates and numbers.

First stop of the day is Hill 60 and the Caterpillar Crater, a place of massive strategic importance that changed hands several times during the conflict. The number in the name refers to the fact that this lump is a mere 60 metres above sea level but thanks to the general flat of the land it commands a vital view over Ypres. Time and nature have mellowed the scars of war but the area is still torn with holes and craters, the Caterpillar Crater is a peaceful wooded glade with a pond at it’s centre now, with a calming serenade of frogs, and for the briefest moment it’s possible to forget that the place is a mass grave of men mulched into the mud by shells and mines, although that tranquility seems appropriate. A focus for the horrors of tunnel warfare, where miners were brought in to dig tunnels in order to place massive mines under enemy positions the Caterpillar Crater is nearly 80 metres in diameter and over 15 metres deep and it was just one of the 17 mines fired to signal the start of the Battle of Messines offensive in 1917 killing about 10,000 men, with a blast audible in London.

From here we move on to the Hill 62 memorial to commemorate the role of Canadian soldiers defending this piece of high ground above Ypres. A large granite block in the middle of a circle of grass with an outlook over the city it manages to be poignant and beautiful at the same time. With no overt insignia of war it leaves the visitor with their thoughts at what might have happened at this picturesque place that would now be a good spot for a picnic.

We continue the tour, past Sanctuary Wood, Polygon and Buttes New British Cemeteries, whistlestop through Passchendaele Memorial Museum and their trench reconstructions without even the time to stop in the gift shop and buy something with a poppy on, and on to the famous Tyne Cot Cemetery. Nearly 12,000 soldiers are buried here, but that’s as nothing compared to the 35,000 men whose graves aren’t known that are commemorated on the memorial wall at the rear of the cemetery.

The statistics and numbers have been slowly accumulating through the day like a rolling jackpot and almost become meaningless as they start to numb the brain into a dull fuzzy incomprehension. But it’s the reminders that even after a century the Great War is still very much alive on a day-to-day basis that bring home the true unimaginable scale of the conflict. It’s in the rum ration bottle necks being used as wire fence tensioners, it’s in the people still being killed by ploughed ordnance, it’s in the dead bodies still being uncovered, it’s in the barbed-wire stakes still being used as barbed-wire stakes, it’s the concrete blocks of a German bunker being repurposed into a driveway. It’s a name that’s only ever been in books that becomes searingly real when you cycle through it and you’re convinced you can feel the history seeping up through the ground to stain your bones.

This is your suffering.

Hearing an endless stream of stories about how it took hundreds of thousands of men to make slow advances up a hill makes the infinite layering of cycling rhetoric about the pain and effort and suffering pedaling up slopes look a little pale. The futile insignificance of battling up 40 Hills yesterday is not lost. Adversity is not in the ersatz insignia of lions and flags on your lightweight carbon bike you put on top of your Audi after 64 miles of limp misery in the drizzle. None of that fake jeopardy you spread on thick to add meaning to a safe life is a hardship, even if you do get a medal at the end. Especially if you do get a medal, pause for a moment to think about those that actually earned theirs. Stop pretending. No amount of artful photography of cyclists looking a bit cold and weary will make it real.

Come to Belgium and experience actual suffering.

Jo Burt has spent the majority of his life riding bikes, drawing bikes and writing about bikes. When he's not scribbling pictures for the whole gamut of cycling media he writes words about them for road.cc and when he's not doing either of those he's pedaling. Then in whatever spare minutes there are in between he's agonizing over getting his socks, cycling cap and bar-tape to coordinate just so. And is quietly disappointed that yours don't He rides and races road bikes a bit, cyclo-cross bikes a lot and mountainbikes a fair bit too. Would rather be up a mountain.

Latest Comments

- David9694 3 sec ago

"Make me to know your ways, O LORD; teach me your paths." - Psalm 25:4

- David9694 11 min 25 sec ago

Come and join in the fun over here. https://road.cc/content/forum/reform-party-and-uks-lurch-towards-fascism...

- anotherflat 26 min 7 sec ago

So uninsured?...

- visionset 33 min 15 sec ago

Oh excellent. More expensive tech to hand over to the bike jacker.

- Vo2Maxi 1 hour 11 min ago

Armstrong has never told the FULL truth.

- Bigtwin 1 hour 21 min ago

Is the relvant authorites are so inept they can't even efficiently tax someone who sole relevant skill is that they drive a car quickly in a circle...

- Bigtwin 1 hour 29 min ago

Clarkson. Fat moron's icon talking tocix ill-informed bollix shocker. If ever there was someone who should just be put out to grass with the rest...

- Garethhall74 2 hours 5 min ago

It will be interesting what new features or functions the new Booky and Roam V3's have, plus if any new functions get added to the element app....

- Rendel Harris 2 hours 37 min ago

I know they're the dregs but that really would be scraping the bottom of the barrel.

- Dnnnnnn 3 hours 19 min ago

+1 for the physio. I'd knee problems a few years back - except the problem wasn't really my knees, it was muscles above and below. I doubt I'd have...

Add new comment

22 comments

Beautifully written, evocative piece.

Would it be possible to have the route details or a GPS file?

Thanks

Found this if it is of any use

http://www.gpsies.com/map.do?fileId=dhrteoxtmxnuavbz

Fantastic article and inspired me to get out there and do it myself next year - thank you.

Good writing there sir. Well done you.

Just a small detail, but one worth noting. That bottle neck is more likely to be an insulator for when they run some lectric through the barbed. In the grand scheme of things it may seem trivial. Bless them all

It may have been 100 years ago, but the vast majority were not Professional Soldiers, unlike they are today. They were disposable, that should always be remembered.

I joined the military in '83 and I'm still serving. I didn't spot any 'sentimentalist hogwash', just a very well constructed and enjoyable read.

Each to their own I guess.

What a wonderfully well written piece. I will always remember my visit to leper and the ceremony at the Menin Gate, especially poignant for me as there are family names listed on it.

I appreciate some people will not/or refuse to understand the "sentimentalist hogwash" involved in trying to come to terms with what our forebears went through, but your piece did it justice and then some.

Thank you

I joined the military in 1984, discharged in 2006. I am sorry vecchiojo, but what a load of sentimentalist hogwash. I was going to expand, but I can feel the anger rising! It was a 100 years ago get over it.

'We will remember them'.

I joined the Army in1971 and left in 1981 and still remember those that gave and support those that are still expected to give their lives. It may be 100 years ago but it's as relevant now as it was then.

You're one of those that Churchill had in mind when he talked about 'those who ignore history being doomed to repeat it'.

You are of course entitled to your opinion but I hope your posting name doesn't mean you're linked to the Cyclist magazine, because if you are you've just lost them a reader and subscriber.

Beautifully put, I wept at the Menin Gate as a 15 year old. That is one school trip that I shall always remember. Did your tour visit the German cemetaries too? A greater contrast to the Allied cemetaries is difficult to imagine.

I intend to visit again...

Well that puts things into perspective. Wow. Really well written.

Fantastic Blog VecchioJo, really lovely.

That dust you speak of gets everywhere, I seem to have some here.

Beautifully written. As Winston Churchill said of Ypres: 'A more sacred place for the British race does not exist.'

I spent a week touring the area with my family a few years ago, tracking down the graves of my great grandad and his brother. Visiting the memorials and cemeteries is an almost overpoweringly emotional experience. One of the most affecting for me was the German cemetery at Vladslo where Kathe Kollwitz's sculpture 'The Grieving Parents' is installed. In that graveyard are two British graves and I couldn't find out how they came to be there, but they are very well kept.

Later in the week the Tour passes Verdun, where the French army stood (contrary to popular belief). The slaughter there eclipsed even Ypres and the Somme. The Ossuary (bone house) at Verdun houses the names of the missing and remains of the unidentified. Built in the shape of an immense artillery shell it is a quite staggering monument.

It will be a thought provoking few days as the tour wends its way down the Western Front.

Great piece of writing. Thank you.

Beautifully written. I was in Ypres two weeks ago, being there does bring a lot of deep thoughts to you. A sombre place to be.

This is excellent.

A superb blog

Bravo.