- News

- Reviews

- Bikes

- Components

- Bar tape & grips

- Bottom brackets

- Brake & gear cables

- Brake & STI levers

- Brake pads & spares

- Brakes

- Cassettes & freewheels

- Chains

- Chainsets & chainrings

- Derailleurs - front

- Derailleurs - rear

- Forks

- Gear levers & shifters

- Groupsets

- Handlebars & extensions

- Headsets

- Hubs

- Inner tubes

- Pedals

- Quick releases & skewers

- Saddles

- Seatposts

- Stems

- Wheels

- Tyres

- Tubeless valves

- Accessories

- Accessories - misc

- Computer mounts

- Bags

- Bar ends

- Bike bags & cases

- Bottle cages

- Bottles

- Cameras

- Car racks

- Child seats

- Computers

- Glasses

- GPS units

- Helmets

- Lights - front

- Lights - rear

- Lights - sets

- Locks

- Mirrors

- Mudguards

- Racks

- Pumps & CO2 inflators

- Puncture kits

- Reflectives

- Smart watches

- Stands and racks

- Trailers

- Clothing

- Health, fitness and nutrition

- Tools and workshop

- Miscellaneous

- Buyers Guides

- Features

- Forum

- Recommends

- Podcast

Jesse Ewart wins stage four, 2024 Tour of Thailand, and syringe

Jesse Ewart wins stage four, 2024 Tour of Thailand, and syringeIs EPO making a comeback? Asia-based Irish cyclist banned for three years as blood booster found in doping sample after Astana development rider’s CERA positive

Fashion, they say, is cyclical. So too, it appears, is doping in cycling. Cortisone and testosterone, mainstays of the 1970s and 1980s (though they have lurked in the background for much longer), enjoyed a public renaissance over the past decade thanks to jiffy bags, missing laptops, and medical tribunals.

Meanwhile, in the early 2000s, the seemingly old-fashioned and rather gory use of blood transfusions suddenly became flavour of the month once again among the sport’s biggest names, after the UCI finally introduced a test for EPO, the performance enhancer of choice for the rocket-fuelled, big ring-climbing peloton of the 1990s.

And now, over two decades later, EPO itself is back in the news, in the wake of three quick-fire positive tests for the banned blood booster among either amateur or semi-professional cyclists since May.

A synthetic version of the naturally produced hormone that stimulates the production of those all-important oxygen-carrying red blood cells, Erythropoietin (EPO, or Edgar Allan, if you prefer to use the rather transparent codename ascribed to it by Lance Armstrong, Tyler Hamilton, and friends during those halcyon ‘Motoman’ days at US Postal) was seemingly ubiquitous in the pro peloton of the 1990s and 2000s and, in the words of Colombian climbing star Lucho Herrera, allowed “riders with fat arses to climb cols like aeroplanes” at cycling’s biggest races.

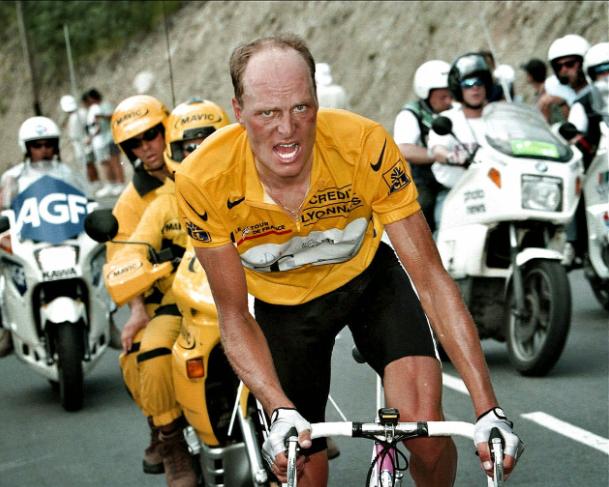

‘Mr 60 per cent’ Bjarne Riis, in the yellow jersey, the big ring, and on a boat-load of EPO at the 1996 Tour de France

But these days, officially at least, it appears confined to the sport’s fringes and lower semi-professional tiers, as evidenced by the recent positives announced by the UCI.

This week, it was the turn of Australian-born Irish rider Jesse Ewart to be slapped with a three-year suspension from the UCI after he returned an Adverse Analytical Finding (AAF) for the blood booster after a doping control test on 26 January, the same day the 30-year-old won the opening stage of the UAE-based Tour of Sharjah, a UCI 2.2 ranked race.

Ewart, who since 2016 has based his entire career racing at UCI Continental level (cycling’s third tier) in Asia, has been part of the Malaysia-based Terengganu Cycling Team for the past two years.

After an almost career-ending crash in Romania in 2022 – which saw a motorist driving at 80kph in a 30kph zone hit him head-on during a training ride before the Sibiu Tour, which left him with five fractured vertebrae and a cracked skull – Ewart had enjoyed a successful 2024 season, winning his first race of the season in the UAE (his first victory since 2019), finishing seventh overall, before winning stage four of the Tour of Thailand in a small group sprint.

Ewart wins stage four of the 2024 Tour of Thailand

However, those 2024 results have all been struck from the record, after Sport Integrity Australia confirmed that the 30-year-old returned a positive post-stage doping test for EPO following his win at the Tour of Sharjah, and will be banned from the sport until 15 May 2027, three years on from the date his provisional suspension was enacted. He has also been fined 7,000 CHF.

“The substance EPO is a Non-Specified Substance and is prohibited at all times,” the Sport Integrity Australia statement said.

“Mr Ewart’s three-year period of Ineligibility commenced on 16 May 2024. Mr Ewart is ineligible to participate in any sports that have adopted a World Anti-Doping Code compliant anti-doping policy until 15 May 2027.

“He is also not permitted to compete in a non-Signatory professional league or Event organised by a non-Signatory International Event organisation or a non-Signatory national-level event organisation.”

The little-known Irish rider’s suspension for EPO comes just over a week after similarly obscure 22-year-old Kazakh rider Ilkhan Dostiyev was sacked by Astana Qazaqstan’s development team after testing positive for CERA, an EPO variant responsible for a host of positive tests in the late 2000s.

In 2008, Riccardo Riccò, Emanuele Sella (both of whom lit up that year’s Giro d’Italia), Stefan Schumacher (winner of two Tour de France stages), Bernhard Kohl (third place and the King of the Mountains at the Tour), Tour stage winner Leonardo Piepoli, and classics legend Davide Rebellin all tested positive for CERA.

Earlier this month it was confirmed that Dostiyev – who had secured a series of impressive results throughout 2024, including finishing second to promising Brit Joe Blackmore at the Tour of Rwanda and winning the Turul Romaniei stage race before jumping up to Astana’s WorldTour squad for two races in Italy and China – could face a four-year ban for his use of the blood boosting drug.

Announcing his sacking, Astana (whose general manager, Alexander Vinokourov, was banned for a year in 2008 for blood doping at the Tour de France, before returning to win more Tour stages, classics, and an Olympic gold medal at 38) said the news of Dostiyev’s doping came as a “shock and disappointment”, and that the team does its “best to ensure that athletes understand not only the consequences of using doping but also the absurdity of attempting to violate anti-doping rules”.

> Former pro cyclist tests positive for EPO after Gran Fondo wins

And in May, it was announced that former pro Nicola Genovese, who rode at UCI Continental level for the small D’Amico-Bottecchia team during a short-lived pro career in 2016 and 2017, had also tested positive for EPO following several notable Gran Fondo performances.

Genovese had won a series of Gran Fondo amateur races in Italy this year, prompting Italian cycling website TuttobiciWeb to describe the 30-year-old’s “spectacular” performances as evidence “Nicola Genovese is reborn with determination from his ashes and does so by returning stronger than before”.

But while the small fish continue to be caught using what appears to be yesterday’s methods, the last time a male professional in cycling’s top two tiers was caught using EPO through an anti-doping test was Delko Marseille’s former FDJ and Astana rider, and Paris-Nice stage winner, Rémy Di Grégorio in 2018.

2015, meanwhile, saw positive EPO tests for AG2R’s Lloyd Mondory, Androni’s Davide Appollonio, and Katusha’s Giampaulo Caruso (based on a re-test from 2012).

However, in recent years, high-profile positives have been contained to Nairo Quintana’s in-competition infringement for painkiller tramadol (which doesn’t carry a ban in any case), and Toon Aerts and Shari Bossuyt’s positive tests for the cancer drug Letrozole.

At the moment, targeted anti-doping investigations, rather than testing, appear to be the most likely way of catching big names in the act, evidenced by Tour de France stage winner and grand tour podium finisher Miguel Ángel López’s four-year ban for possessing and using the human growth hormone menotropin (revealed as part of a probe into Spanish drug trafficking ring), as well as EF Education-EasyPost rider Andrea Piccolo’s recent arrest for trying to smuggle HGH into Italy.

After obtaining a PhD, lecturing, and hosting a history podcast at Queen’s University Belfast, Ryan joined road.cc in December 2021 and since then has kept the site’s readers and listeners informed and enthralled (well at least occasionally) on news, the live blog, and the road.cc Podcast. After boarding a wrong bus at the world championships and ruining a good pair of jeans at the cyclocross, he now serves as road.cc’s senior news writer. Before his foray into cycling journalism, he wallowed in the equally pitiless world of academia, where he wrote a book about Victorian politics and droned on about cycling and bikes to classes of bored students (while taking every chance he could get to talk about cycling in print or on the radio). He can be found riding his bike very slowly around the narrow, scenic country lanes of Co. Down.

Latest Comments

- David9694 41 min 51 sec ago

Down my way, a 200 yard bus gate or 20 mph limit extinguishes all economic and domestic life, so I assume Paris centre-ville has been rendered a...

- Miller 1 hour 31 min ago

Thanks. I have no idea about the bike which is being held at a local police station. I can't imagine it's in good shape. I remember nothing about...

- TimC340 1 hour 44 min ago

Why didn't RoadCC have a review sample before this article? Then it would be less speculation and more fact. Never mind, DCRainmaker and DesFit...

- mark1a 5 hours 35 min ago

I think the best thing I did when I rode the sportive in 2016 (163km edition from Busigny with all 29 cobbled secteurs) was to fit Elite Pria Pavé...

- mark1a 5 hours 55 min ago

On the plus side, I haven't taken out any over 50 life insurance plans or felt compelled to arrange any prepaid funerals over the weekend, or...

- chrisonabike 7 hours 44 min ago

Edinburgh has formal booking, they added putting "bike" or "cargo bike" in the car registration section. (I've just checked again and oddly you...

- ktache 8 hours 5 min ago

I don't think I will be converting anytime soon, but thanks for the report, and I wouldn't mind if you update with real world use.

- Freddy56 8 hours 50 min ago

I would say it more a jersey than a jacket. Super warm chest insulated with the sleeves are lighter, more like a roubaix top, so, ideal spring wear...

- PenLaw 9 hours 8 min ago

Nigel Farage is simply pleasing his main sponsors, that being big oil and their Telegraph/Express pseudo employees....

- Rendel Harris 10 hours 26 sec ago

I don't know if they would specifically target them but I do know that travelling on local services around London a couple of times a week, once or...

Add new comment

4 comments

I need EPO and anything else they can have my pee

Kudos for all the info and an interesting topic - you really know your stuff. But at times it becomes hard to digest because so much info is being crammed into a single sentence. As an example the title - I'd have preferred something like "Is EPO making a comeback? Another rider caught using blood booster a week after Astana development rider’s CERA positive."

Correct me if I am wrong: epo is storing your oxygen rich blood then transfusing it back into an oxygen starved body (post racing) to effectively get fresh again. Systematically doing this as a team among other teams as it was in the early 2000s is one thing but doing it to oneself every evening is sad and desperate. No one should be pursuing ill-begotten advantages anymore.

No, that's blood doping, which is used to increase your red blood (oxygen carrying) cell count so that your muscles get a higher level of oxygen to fuel them. EPO is the injection of synthetic erythropoietin; natural erythropoietin is released by the kidneys to combat hypoxia, so EPO keeps hypoxia at bay for longer, allowing athletes to train or indeed race at maximum levels for longer than they could without.