- News

- Reviews

- Bikes

- Components

- Bar tape & grips

- Bottom brackets

- Brake & gear cables

- Brake & STI levers

- Brake pads & spares

- Brakes

- Cassettes & freewheels

- Chains

- Chainsets & chainrings

- Derailleurs - front

- Derailleurs - rear

- Forks

- Gear levers & shifters

- Groupsets

- Handlebars & extensions

- Headsets

- Hubs

- Inner tubes

- Pedals

- Quick releases & skewers

- Saddles

- Seatposts

- Stems

- Wheels

- Tyres

- Tubeless valves

- Accessories

- Accessories - misc

- Computer mounts

- Bags

- Bar ends

- Bike bags & cases

- Bottle cages

- Bottles

- Cameras

- Car racks

- Child seats

- Computers

- Glasses

- GPS units

- Helmets

- Lights - front

- Lights - rear

- Lights - sets

- Locks

- Mirrors

- Mudguards

- Racks

- Pumps & CO2 inflators

- Puncture kits

- Reflectives

- Smart watches

- Stands and racks

- Trailers

- Clothing

- Health, fitness and nutrition

- Tools and workshop

- Miscellaneous

- Buyers Guides

- Features

- Forum

- Recommends

- Podcast

review

£20.00

VERDICT:

Standard biography and justification of reformed doper – but also the best insight yet into the challenges of running a team

Weight:

600g

Contact:

At road.cc every product is thoroughly tested for as long as it takes to get a proper insight into how well it works. Our reviewers are experienced cyclists that we trust to be objective. While we strive to ensure that opinions expressed are backed up by facts, reviews are by their nature an informed opinion, not a definitive verdict. We don't intentionally try to break anything (except locks) but we do try to look for weak points in any design. The overall score is not just an average of the other scores: it reflects both a product's function and value – with value determined by how a product compares with items of similar spec, quality, and price.

What the road.cc scores meanGood scores are more common than bad, because fortunately good products are more common than bad.

- Exceptional

- Excellent

- Very Good

- Good

- Quite good

- Average

- Not so good

- Poor

- Bad

- Appalling

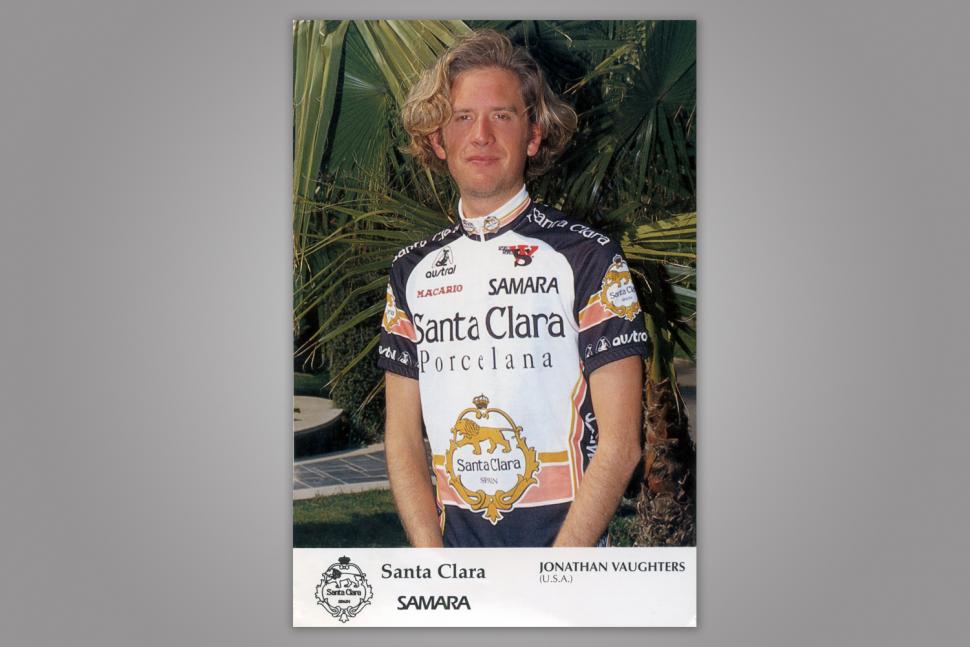

Autobiographies from reformed dopers are now commonplace, which means that One Way ticket won't count as an exposé; however, books that reveal the machinations behind the scenes of a cycling team are less common. While it is hard to get excited about Vaughters' cycling career, fortunately for us he has encountered more than his fair share of business-related drama in his life as a team principal – and we don't normally get to hear about that side from such a key player.

- Pros: One of the most revealing books about the business of running a team

- Cons: It suffers from being written by yet another reformed doper

There has been a relentless stream of autobiographies from former professional cyclists who admit to taking drugs but are now 'reformed'. I would like to think that these will eventually lose their appeal to all involved, but there is no sign of that happening yet. At least this one from Jonathan Vaughters has a point of difference, because he moved on to set up and lead a new team and so is able to discuss another side of the sport. The first part of this book covers Vaughters' rise up the cycling ranks, and the second reveals the challenges of managing a professional team.

The story of Vaughters' early years is interesting enough and eminently readable (thanks in part to input from renowned journalist Jeremy Whittle), but it is his involvement with drugs and other drug takers that overshadows his career and inevitably makes the headlines. You have to decide if you want to read the latest 'revelations' that we have come to expect from that generation of cyclists – and to 'reward' said cyclist by buying the book.

© Jonathan Vaughters

Inevitably, events over the last few years have reduced the impact of any drug-related disclosures – even those from the time he spent sharing a room with Lance Armstrong, who warned him not to 'go write a book about this shit or something'.

Vaughters starts off by being full of natural talent and innocence, but the awareness of enhanced performances and the associated testing soon develops: a blood test at the American Olympic Training Center revealed a high haematocrit level, and such was his naivety that Vaughters had to ask the doctors to explain why they thought that he might have had blood transfusions.

Later, after making the obligatory move to Europe that would be required to progress up the ladder, further blood tests revealed 'enormous VO2 max, enormous left ventricle and lots of hemogolobina', and if 'professional racing was all about oxygen delivery ... I had a great body for doing just that'. In fact, so impressed were his Spanish team that they promoted him into the pro ranks immediately; not only that, they wanted him to ride the Vuelta a Espana that year!

As he tells it, Vaughters' story follows a depressingly familiar pattern, with gradual awareness and then acceptance of performance-enhancing drugs – especially EPO. 'I realised that the unwritten rule of the peloton was "cheat, just not too much".' The extent to which you are prepared to believe or accept this reluctant progression is probably going to depend on what you think should be done about historic drug abuse, and how you want the protagonists to be treated.

Vaughters himself states that 'everyone involved in the professional sport of road cycling during that era has the cloud of suspicion hanging over them. One of the reasons I wrote this book is to acknowledge the part that I played in the creation of that cloud, and to document the things I have done since in an effort to make amends.'

Unfortunately for Vaughters, many people's view of his book will be pre-determined by their view of cycling's drug users rather than by the quality of the book.

> Buyer's Guide: 33 of the best books about cycling

Vaughters is better known these days in his role as head of a pro team, and the desire to 'create the Slipstream cycling team [was] based on the belief that people wanted to make an ethical choice. If you go into a supermarket, there's a big stack of beautiful, yellow bananas, and then there's the smaller bananas – maybe a little brown – and they're the organic ones, costing twice as much as the big yellow chemicals-induced bananas. But people still choose them.'

While this may be a laudable stance, for me it was undermined a little by the fact that Vaughters himself didn't come clean publicly until many years later. To some extent he was right, as was shown by the support that the team generated when it turned to crowdfunding in order to fund its future.

It is this coverage of his life after being a professional cyclist that increased this book's appeal for me: there are a few books from cyclists who have become directeur sportives, such as Sean Yates and Allan Peiper, but very few from those who became a team principal. Johan Bruyneel and Bjarne Riis come to mind, but it is a short list.

The result is that you get very little of what a directeur sportive (DS) might write about, such as the inside line on various significant race results – but you do get quite a lot more background information on some of the high-profile stories to which Vaughters was a party. The team seems to accept that it might not always make the headlines for winning races, but there are other ways to give your sponsors exposure, such as Vaughters' view on how the sport could be organised better, or even by finishing last.

You also get good background on the 'mergers and acquisitions' and constant battles for sponsorship money that have affected Slipstream Sports more than most teams. I thought that it was the best bit of the book, mainly because you don't often get to read about the business side of a team from someone with so much experience – indeed, probably more of it than he would like.

I had hoped for a bit more of the sort of information that only someone in Vaughters' position would know about, and was frustrated by the lack of significant financial detail, for example. At other times you know that another side of the same story is already in the public domain, so you start to question who to believe.

Vaughters explains why he was so keen to have David Millar on his new team, with the two of them being 'two idealistic entrepreneurs who were able to endure each other for a few years', but not why Millar was not chosen for the Tour de France in his last year; that was a decision by the team DS. You get a lot more on that from Millar himself.

As expected (and hoped for), there is extensive coverage of 'the battle for Brad', and Vaughters is very disparaging of the fledgeling Team Sky's antics and how 'the Wiggins negotiations in 2009 would turn the philosophical difference into a cold war and put us at serious odds with each other'. You can see why Vaughters would choose to make the comments that he did about Wiggins recently when trying to create interest in this book.

Slipstream Sports has a justified reputation for having a different approach, and that is very much in evidence today with the team's involvement in an alternative racing calendar. However, the story ends with the sale of the team to EF Education first, so there is no coverage of any participation in such inspiring events. I suspect that some other teams will be studying the success of that venture with interest.

Verdict

Standard biography and justification of reformed doper – but also the best insight yet into the challenges of running a team

road.cc test report

Make and model: One Way Ticket by Jonathan Vaughters

Size tested: n/a

Tell us what the product is for and who it's aimed at. What do the manufacturers say about it? How does that compare to your own feelings about it?

From Quercus:

ONE WAY TICKET is the story of a man and modern cycling.

Jonathan Vaughters is one of the leading figures in world cycling, a record-breaking mountain climber, Tour de France stage winner and former teammate to Lance Armstrong. He is now manager and influential figurehead of the renowned Education First World Tour team.

In ONE-WAY TICKET: Nine Lives and Two Wheels he describes a journey from driven teenage prodigy, travelling to races in the back of his Dad's station wagon, to an obsessive determination to make it big in European racing – whatever the cost. He tells the story of his transformation from poacher to gamekeeper, detailing his painful decision to finally come clean about his own descent into doping – and to persuade others to do likewise – by providing more than enough shocking testimony to USADA (US Anti-Doping Agency) to explode the Armstrong myth.

Working in collaboration with Jeremy Whittle, former cycling correspondent to The Times, now writing for The Guardian, Vaughters reveals the ease with which, his illusions shattered, he walked away from European racing. He documents his own suffering in races, the trials of establishing a team and mentoring young riders, and the dizzying highs of success in races such as the Tour de France, Giro d'Italia and Paris-Roubaix.

Vaughters' long and winding road mirrors that of cycling itself, as this compelling but troubled sport still struggles, after years of scandal, to restore its credibility. Along the way, he shares his unique experience to lift the lid on a world he has both loathed and loved, detailing the fights and fall-outs with cycling's leading figures, including Lance Armstrong, Pat McQuaid, Johan Bruyneel, Bradley Wiggins and Dave Brailsford.

Tell us some more about the technical aspects of the product?

Title: One way ticket

Author: Jonathan Vaughters

Publisher: Quercus

Date: 27/6/19

Format: Hardback

Pages: 375

ISBN: 9781787477483

Price: £20

Tell us what you particularly liked about the product

The insight into running a team.

Tell us what you particularly disliked about the product

No longer feeling shocked about drug-taking revelations.

Did you enjoy using the product? Yes

Would you consider buying the product? Yes, with some reluctance.

Would you recommend the product to a friend? Yes

Use this box to explain your overall score

It is a perfectly good biography that has the same associated baggage as other books from drug-enhanced riders of the same generation. However, it breaks new ground with coverage of life as a team principal, and that, for me, raises it to 'very good' overall.

About the tester

Age: 59

I usually ride: My best bike is:

I've been riding for: Over 20 years I ride: Most days I would class myself as: Expert

I regularly do the following types of riding: touring, club rides, sportives, general fitness riding

This website offers suitable data: https://www.automobiledimension.com/large-suv-4x4-cars.php

Perhaps park the goods in a US Customs Bonded warehouse and then import them out of there when the tariff nonsense settles down?...

Good to see a road.cc review of what must be one of the UK's best-selling 'proper' road bikes. 6/10 feels a little harsh though: the tyres could be...

Another thing ruined by the Americans

Nice to see WvA featuring in the finale.

I have known more than one elder statesman of the club die of a heart failure while out on a ride. Sometimes I feel that's about to happen to me,...

Via the "wireless active steering system".

137m is the farthest I have observed when quickly looking at the Garmin unit....

Yours worked wonders, but if you insist, I'll hop to it...why the need for extra police? Did the fire brigade bottle it?

As if Tadej Pogacar's slavery-supporting jersey is any different...