- News

- Reviews

- Bikes

- Accessories

- Accessories - misc

- Computer mounts

- Bags

- Bar ends

- Bike bags & cases

- Bottle cages

- Bottles

- Cameras

- Car racks

- Child seats

- Computers

- Glasses

- GPS units

- Helmets

- Lights - front

- Lights - rear

- Lights - sets

- Locks

- Mirrors

- Mudguards

- Racks

- Pumps & CO2 inflators

- Puncture kits

- Reflectives

- Smart watches

- Stands and racks

- Trailers

- Clothing

- Components

- Bar tape & grips

- Bottom brackets

- Brake & gear cables

- Brake & STI levers

- Brake pads & spares

- Brakes

- Cassettes & freewheels

- Chains

- Chainsets & chainrings

- Derailleurs - front

- Derailleurs - rear

- Forks

- Gear levers & shifters

- Groupsets

- Handlebars & extensions

- Headsets

- Hubs

- Inner tubes

- Pedals

- Quick releases & skewers

- Saddles

- Seatposts

- Stems

- Wheels

- Tyres

- Health, fitness and nutrition

- Tools and workshop

- Miscellaneous

- Cross country mountain bikes

- Tubeless valves

- Buyers Guides

- Features

- Forum

- Recommends

- Podcast

TECH NEWS

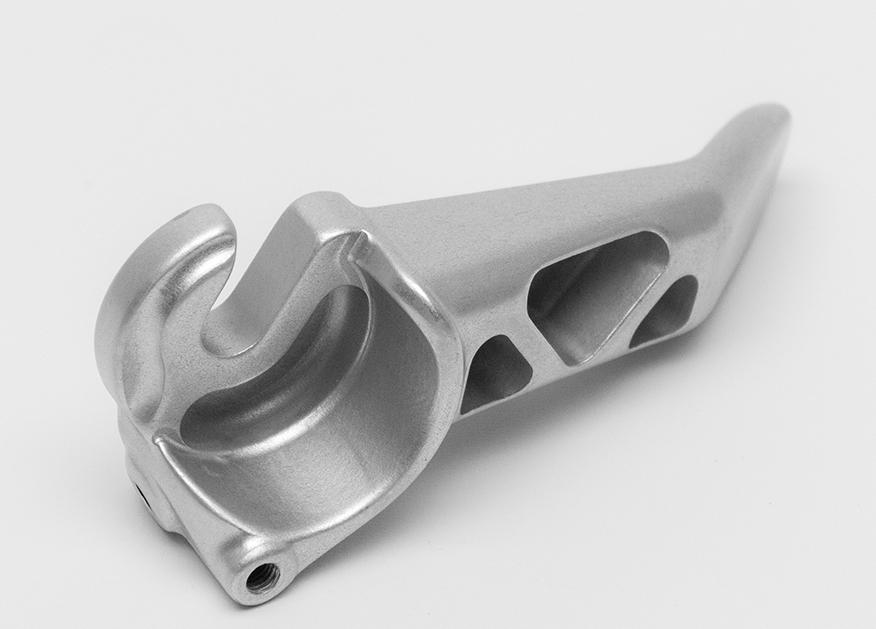

ALLITE_Grvl_Frame_3_Stripped_MED

ALLITE_Grvl_Frame_3_Stripped_MEDAllite launches ‘Super Magnesium’ alloy: lighter and stiffer than aluminium and less expensive than carbon fibre

The humble bicycle has come a long way in the last hundred years but it’s the material developments in the past couple of decades that has arguably produced the biggest evolution, with bikes getting lighter and stronger.

A US company reckons it has developed a new material that could lead to further evolution. It’s called Super Magnesium and is an all-new proprietary alloy that is claimed to be 33% lighter than aluminium as well as being stiffer and stronger, pound for pound, and less expensive than carbon fibre.

- Is magnesium the bike material of the future?

Allite will use the Interbike show to unveil its new alloy to hopefully garner some interest from bicycle brands into using its new wonder material for manufacturing bikes. The new material was first developed in 2006 and it has already been put to use in classified defence and aerospace applications. It hopes the cycling world will be similarly interested.

It’s not the first time the benefits of magnesium have been touted in the cycling industry (Kirk Precision anyone?) but Allite is telling is its new material offers some big benefits including strength, weight and sustainability - compared to carbon fibre it is more eco-friendly and is 100% recyclable.

“We are thrilled to unveil Allite Super Magnesium and all of the superior benefits that it provides to brands and products across a variety of industries,” said Bruno Maier, President of Allite, Inc. “With an exceptional strength-to-weight ratio and high-performance composition, Allite Super Magnesium is simply the best choice for any distinguished brand seeking materials to make their products lighter, faster, stronger, and more environmentally friendly.”

While we’ve seen magnesium bicycle frames in the past, could we be set for a return of this material? Dr Alan Luo of the Ohio State University says it has a distinct appeal. “The superior benefits of magnesium are becoming more well-known and it is exciting to see Allite Super Magnesium delivering a material that can benefit such a vast array of industries. In addition to being earth-friendly, magnesium has increased solubility, and is stronger than other comparable materials, making it a wise choice for the cycling industry and beyond.”

At the moment you can’t buy a bike made from Super Magnesium but when or if bike brands utilise it the company is confident the price will be comparable with aluminium but cheaper than carbon fibre. But the real test will be how the new alloy rides, and for that, we’ll have to wait a while.

But it does sound promising. What do you think? Let us know below.

John Stevenson adds:

Crunching the numbers on Super Magnesium

With any material that's supposed to be the Next Big Thing for bike applications, the devil is always in the detail. Allite's initial announcement of Super Magnesium is light on detail — and that's being kind.

Fortunately there's a bit more on their website, which details some of the classifications and properties of the three magnesium alloys they're calling Super Magnesium.

These alloys have designations AE81, ZE62 and WE54. In magnesium alloys, A stands for aluminium, W for Yttrium, Z for zinc and E for rare earths, the group of metals that includes scandium which was going to be the Next Big Thing as an additive to aluminium alloys a few years ago.

The numbers indicate the rough percentage of the alloying element, so AE81 is eight percent aluminium and one percent rare earths.

So we can see that what we have here are magnesium-aluminium, magnesium-yttrium and magnesium-zinc alloys, each with a bit of rare earths to fine-tune their properties.

Here are the mechanical properties of the three Super Magnesium alloys compared with 6082 aluminium, which is quite commonly used in bike frames.

| Property | ASM AE81 | ASM ZE62 | ASM WE54 | Al 6082 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Density (d, g/cm3) | 1.825 | 1.84 | 1.84 | 2.7 |

| Elastic Modulus (E, GPa) | 46 | 48 | 48 | 70 |

| Yield Strength (YS, MPa) | 240 | 310 | 200 | 255 |

| Ultimate Tensile Strength (St, MPa) | 335 | 355 | 302 | 300 |

| Elongation (ef, %) | 11 | 20 | 4 | 9 |

These are interesting raw numbers that indicate the Super Magnesium alloys are in the same ballpark as aluminium for strength and brittleness (indicated by ef, elongation at failure). The lower Young's modulus means they're less stiff, but that's easily dealt with by using more material in bigger tubes, just as aluminium is used in larger tube diameters than steel. With the material being less dense, Super Magnesium could still come out ahead on the weight of the final piece.

However, the raw properties of a material never tell the whole story. What happens when you weld the material into a bike frame is vitally important. In some aluminium alloys, for example, the heat of welding causes the alloying elements to migrate away from the weld zone in a way that's not restored by subsequent heat treatment. This is also a problem with the metal matrix composites that were going to be the Next Big Thing back in the 1990s.

Then there's the material's behaviour under cyclic loading. Repeated loading and unloading leads to the phenomenon known as metal fatigue, which is what often kills metal bike components. Allite hasn't, as far as we can tell, released any numbers for the fatigue behaviour of Super Magnesium.

A viable material for bike frames and components also has to be corrosion-resistant. This used to be a big problem for magnesium bike parts; I had a pair of early RockShox Mag 21 fork sliders practically destroyed by a winter of riding roads that had been salted. Allite claims the Super Magnesium alloys have "corrosion rates of the same order as some corrosion-resistant aluminium alloys" and can be be treated by plasma electrolytic oxidation (PEO) to further protect them. PEO also improves wear and fatigue resistance, Allite says.

Super Magnesium looks like promising stuff, then, but we have been here before numerous times. As well as the materials mentioned above that eventually sunk without trace, aluminium-lithium alloys had a brief moment in the sun back in the 1990s too, and the properties of beryllium had a couple of bike makers excited for a while, until they realised that there really wasn't much of a market for bike frames that cost $20,000.

Fun fact: There are magnesium alloys that include thorium, a metal that's been suggested as the basis for nuclear reactors that couldn't produce weaponisable material. However, any magnesium alloy with more than two percent thorium has to be treated as a radioactive material, so we're unlikely to see it on bikes any time soon.

David worked on the road.cc tech team from 2012-2020. Previously he was editor of Bikemagic.com and before that staff writer at RCUK. He's a seasoned cyclist of all disciplines, from road to mountain biking, touring to cyclo-cross, he only wishes he had time to ride them all. He's mildly competitive, though he'll never admit it, and is a frequent road racer but is too lazy to do really well. He currently resides in the Cotswolds, and you can now find him over on his own YouTube channel David Arthur - Just Ride Bikes.

Latest Comments

- bikeman01 13 min 29 sec ago

Re-deployed on Twitter duty?

- Hirsute 19 min 3 sec ago

Last clip especially for wtjs !! https://youtu.be/XKD4kI1yDMg?si=5qCj5QI72pVCR4WN

- bikeman01 20 min 41 sec ago

And had he not shouted 'go back to Africa', the Police would have dismissed this.

- kil0ran 1 hour 13 min ago

Your sub is tied to the country your credit card is registered to so it's not just about IP addresses.

- brooksby 1 hour 17 min ago

Maybe... I was taking a slightly wider interpretation, just *bringing* Nazis and Hitler into an argument

- mdavidford 1 hour 58 min ago

Presumably not featuring the miserable- looking pair who've been made to wear their kit?

- chrisonabike 3 hours 39 min ago

There's a lot about, and once you're "woke" or sensitised to it it's hard not to see it. However I think it's essentially a category difference if...

- chrisonabike 4 hours 5 min ago

Good point. Although are they organised? Also fruitcakes have something to be said for them, even if they're a bit nutty.

Add new comment

23 comments

It'd have to go some way to bettering the daddy of alu frames, that being those from Principia. They were knocking out 1160g frames as early as 1992, their oversized tubed RS6 Pro was 1120g, that was 2002.

If someone can build with this material to get anywhere near the quality of the Principia's rocket ship properties with a significant weight saving (oh and using their superb 320g carbon forks) then they'd have a product some would seriously consider over carbon.

What was it like when dinosaurs walked the Earth?

First pic in this link is one of these built up: https://cyclingtips.com/2018/09/interbike-2018-day-two-magnesium-is-back...

The only steel alloys I know of with titanium as an alloying element are High Speed steel and Tool steels, neither of which would make good bike rim material.

I just wonder how crash tolerant the material vs other material, I'm assuming it's similar to aluminum? And what about the corrosion that was so prevalent with the old magnesium bike frames of the 90's?

Anybody else remember the Kirk Precision from the 80's?

Sounds like it could be a good material for wheel rims, it's already being used for race cars and bikes, with slightly less complex forces than bike frames they could be a fairly good solution, taking thirtyish percent from the weight of an aluminium wheel would be pretty impressive without going to carbon.

Wasn't there talk not that long ago of a steel that had a high proportion of titanium in it making it significantly stronger and lighter? I've been wondering when we'd see that come along.

Some bicycle components are made from magnesium. I've some Welgo magnesium pedals on my BMX cruiser race bike. They are incredibly light compared with the pedals of more conventional alloy on my 20" BMX. They were covered in some kind of corrosion protective layer but that's worn off now after a few seasons of use, but I haven't spotted any signs of corrosion. I seem to recall (from my materials technology module when I studied engineering decades ago) that corrosion in magnesium components can penetrate into the structure, without being easily visible. At least with aluminium, when corrosion begins to be an issue it leaves tell-tale signs on the surface and the same is true for steel of course.

The main issue for a frame material is specific stiffness, i.e. the Young's modulus divided by the density. Frame materials such as steel, aluminium and titanium all have similar specific stiffnesses, and this magnesium alloy comes in the same range. So in principle you can build frames from each down to a similar weight. In practice you can't due to secondary characteristics. For magnesium, though, the low density could allow the tubes to be massively oversized whilst remaining thick enough not to buckle or dent, so could indeed give a lighter frame than the others.

Carbon fibre has a higher specific stiffness, which is why carbon frames can be made lighter. There are a few materials around with even higher specific stiffnesses than carbon fibre, but it would be impractical to build a frame from most of them (diamond, anyone?). The one exception is beryllium, which would be the ultimate frame material except that it is extremely toxic and carcinogenic. So I don't expect to see any beryllium bikes around.

Typically I don't lick my bikes so not sure how a beryllium frame would be toxic and carcinogenic.

I hope its less brittle than Scandium

I had a scandium frame that cracked at the top of the head tube about an inch long and the factory wouldn't warranty it stating it was due to fatigue after only 8,000 miles!?

Can't be 3D printed? Crap!

Magnesium alloys have been used for decades for racing motorcycle castings in place of aluminium as a weight saving measure. However they are much more susceptable to corrosion which is why they are not used on production models. Have Allite come up with a magnesium alloy that isnt so susceptable to corrosion? I don't know but if not I wouldn't go anywhere near it.

They say it's corrosion resistant

And, from Yehuda Moon: Arborium (2)

2009-07-28.gif

And, from Yehuda Moon: Arborium (1)

2009-07-27.gif

Just don't let it near a naked flame!

Alloys of aluminium and magnesium have been used for decades to make lightweight wheels for performance cars. Campagnolo even made them for some Ferrari models. Refurbishing them requires a special process that is easy to mess up - so make sure you don't chip your Mg alloy bike frame!

Very interesting.

Currently the lightest frame -I could find: Trek Emonda SLR9- weighs 640 grams,

The lightest aluminium frame (CAAD12 I assume?): Frame 1140 grams. If we can shave off 33% we arrive at 752 grams, roughly 100 grams lighter than the lightest-of-the-lightest carbon frame.

The Giant TCR alloy frame is about 1,050g, so 693g at 33% off

"magnesium has increased solubility"

Not sure I like the sound of that - the idea of a soggy noodle bike frame does not appeal.

It wouldn't be a problem for me, I don't ride in the rain and washing bikes is for losers.

I'm pretty certain that's a typo, Magnesium is very insoluble, maybe it might dissolve over a hundred years!