- News

- Reviews

- Bikes

- Components

- Bar tape & grips

- Bottom brackets

- Brake & gear cables

- Brake & STI levers

- Brake pads & spares

- Brakes

- Cassettes & freewheels

- Chains

- Chainsets & chainrings

- Derailleurs - front

- Derailleurs - rear

- Forks

- Gear levers & shifters

- Groupsets

- Handlebars & extensions

- Headsets

- Hubs

- Inner tubes

- Pedals

- Quick releases & skewers

- Saddles

- Seatposts

- Stems

- Wheels

- Tyres

- Tubeless valves

- Accessories

- Accessories - misc

- Computer mounts

- Bags

- Bar ends

- Bike bags & cases

- Bottle cages

- Bottles

- Cameras

- Car racks

- Child seats

- Computers

- Glasses

- GPS units

- Helmets

- Lights - front

- Lights - rear

- Lights - sets

- Locks

- Mirrors

- Mudguards

- Racks

- Pumps & CO2 inflators

- Puncture kits

- Reflectives

- Smart watches

- Stands and racks

- Trailers

- Clothing

- Health, fitness and nutrition

- Tools and workshop

- Miscellaneous

- Buyers Guides

- Features

- Forum

- Recommends

- Podcast

feature

On the factory floor making cycle clothing at Lusso

On the factory floor making cycle clothing at LussoFast fashion – how eco is your cycle clothing?

As the world’s second most polluting sector, the clothing and textile industry poses one of the greatest risks to both nature and human health, especially in developing countries. It takes an incredible 2,700 litres of water and almost a kilogram of hazardous chemicals to make just one t-shirt, and that’s for a relatively natural (albeit not organic) cotton product. When you start dealing with man-made, plastic-based materials, such as the types of Lycra and polyesters found in cycling garments, the potential harm to life, ecology and water supplies becomes even more acute.

So what are cycle clothing manufacturers doing to address this?

The good news is that some firms right here in the UK are already leading the fight for sustainability.

When it comes to eco-awareness, everything starts with the fabric. While swapping to organic cotton is an obvious solution for many ethical fashion manufacturers, the alternatives aren’t quite so clear when it comes to the kind of technical, synthetic materials used in cycle clothing. However, proving that even performance cycling kit can have ecologically sound origins, Shutt Velo Rapide has started using fabric made from recycled plastic waste collected from the world’s oceans. In fact, as Shutt’s operations manager Dave O’Connor explains, there’s no reason not to use it.

“It’s not difficult to get hold of sustainable technical fabrics at all,” says Dave. "Many of the technical materials used in cycle clothing are readily available and have been for some time. But what hasn’t been available until very recently is the ability to audit that material and understand and identify where that fabric actually came from. It’s one thing to say this t-shirt is fully recycled, but recycled from what and from where?

“We started using ocean waste recycled materials last year and we are now very close to being able to tell the customer where the raw material for a particular batch of jerseys was recovered from which ocean and when. Every single item we offer as part of our custom team wear is available in recycled fabrics, as well as an increasing number of garments on our retail site. The project is ongoing, and we want to get to a point at the end of next year where our entire range is made from recycled materials.”

Money matters

Commercially speaking, from Shutt’s experience and in the cycling market particularly, the use of recycled materials is very much pushing at an open door.

“Since we’ve been selling these products, we’ve noticed that the minute we tell people about where this material has come from, they light up and want it,” says Dave, "because they’re cyclists and they’re environmentally conscious.”

But surely using such an extensively processed fabric must push prices up? Dave says not at all.

“The material commands a slightly higher price but it’s not enough to deter anybody,” he says. "In fact, for the customer, a pair of shorts made from recycled material shouldn’t actually cost any more than shorts made from other fabric. The price varies depending on the technical build and variation of material used, rather than if it's recycled or not.

“At Shutt, we are determined to play an active role in cleaning up our oceans without asking our customers to pay more. The customer will decide if the recycled kit is good enough to invest in and so far, there has been a resounding yes! Of course, it doesn’t stop there. But we know we have a great platform to build on and as customer demand for it continues to grow, it will in turn drive down the price and make it even more affordable for all.”

Social responsibility

Price not being an obstacle is something reiterated by John Harrison, boss of Manchester-based British bike clothing brand Lusso. Lusso is on course to use 50% recycled fabrics in its products by the end of 2020 and already fits pads made from recycled fishing nets. “They cost 50p more than normal, so there’s no excuse not to use them, and they’re fantastically soft,” John says.

But the way that Lusso approaches sustainability that isn’t just about recycled textiles.

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals list 17 criteria, including requirements such as ‘reduced inequalities’ and ‘responsible production and consumption’ in the supply chain. One way manufacturers can ensure their supply chain is ethical is to work with certification bodies, such as Fair Trade or Fair Wear. But even then, manufacturers are still only trusting that workers are being treated properly.

A more direct way – and one which has the added advantage of reducing carbon emissions and thereby satisfying the ‘climate action’ UN SDG – is to bring production much nearer home. That’s a model that has been championed by Lusso since the very start of its 38-year history.

“We’re one of those rare things,” says John, “we’re an actual manufacturer and we make our garments right here in Manchester.

“Depending on demand, we have between 12 and 16 staff making products. All our staff live within 10 miles of the factory and quite a few of them cycle to work, which is great. And everybody in production gets paid the same – we don’t operate a piecework policy or anything like that. We like to think we look after our staff; we must be doing something right because we can’t get rid of them – they won’t leave!”

Carbon footprints

While it might seem unusual to have cycling garments actually made in the UK, in terms of global production and supply chains, things are changing.

“A decade ago Chinese workers were getting paid very poorly, but nowadays that’s not quite the same,” says John. “So even though we pay UK workers more than Far Eastern workers would get, if you add in all the other costs of the supply chain and transporting the products during its production stages – and we don’t spend a lot on marketing or sponsoring a pro team – then we’re not actually that far apart.

“And because we have only ever used UK and European fabrics, our carbon footprint is really small. Chinese-made garments will start with fabric from Italy, that goes to China for manufacturing, it comes back to a distributor in Europe, and then it goes to the retailer. That garment’s carbon footprint can be three times greater than the equivalent Lusso product.”

Even in the final stage – getting the product to the customer – Lusso is a step ahead of many brands. Its packaging is made from cardboard, which is supplied by a company just 25 miles away in Glossop.

As well as reduced carbon footprints, Lusso’s business model also leads on to other sustainability benefits. In some parts of the garment industry, businesses are moving towards a manufacture on demand model, even for individual items. While cycle clothing isn’t quite there yet, Lusso is able to supply bespoke limited-run garments, which necessarily means less wastage.

Another great advantage of in-house production is quality control – problems can be solved instantly, which leads to less waste, increased all-round efficiency and longer-lasting products.

“Some manufacturers use cheaper fabric with less elasticity and cheaper thread, which then starts falling apart quicker and, for the cyclist, might only last 12 months,” says John.

“With our approach using premium quality materials and fabrics – and having complete control and responsibility for the manufacturing process right here – you should get four years out of a pair of shorts. So less waste goes to landfill, the customer actually saves money in the long term, and sustainability is enhanced.”

Make better, wear longer

Indeed, as John says, the easiest way any of us can be more environmentally sound is to limit purchases and really make the most use of our kit. Encouraging customers to invest in better quality, better produced clothing which can be used for a range of functions is the approach Brighton-based brand Morvélo is starting to follow. Its Overland range aims to increase sustainability through versatility.

“Clothing is used up to 36% less than it was 20 years ago and the world is making 400% more clothing than it did 20 years ago,” Morvélo boss Oli Pepper says.

“Overland addresses this by creating sports clothing that is designed to cross over easily into everyday life. Why buy one shirt for daytime and then another for cycling or sports when you can have only one item of clothing that does both? We want the Overland range to enable people to reduce their clothing consumption by at least 50%.”

Morvélo also has very clear plans about how it can make its entire business model almost entirely sustainable, from product manufacturing to garment end-of-life and even rebirth. Ironically, for companies whose commercial success is generally reliant on selling more, Oli recognises that sustainable success will actually mean selling less.

“We are moving all our production to use recycled fabrics from 2021 onwards but, really, this is just the tip of the iceberg and a relatively easy step,” says Oli. “We're also spending a great deal of time and resources researching the circular economy and how products should be designed, not just from recycled fabrics, but how they can extend their life and also what happens at the end of their life. In fact, we have plans for the business to change a great deal in the next 12 months and dramatically reduce the amount of new clothing we produce.

“Our holy grail will be to create clothing from existing resources, designing products for ease of repair and also deconstruction at the end of their life, so they can then be easily recycled or upcycled back into new clothing. It has to be circular and not linear. If you make clothing from recycled fabrics that is great, but it only addresses one part of the problem. The world already makes too much clothing so our focus is on how to address this and yet remain a viable business.”

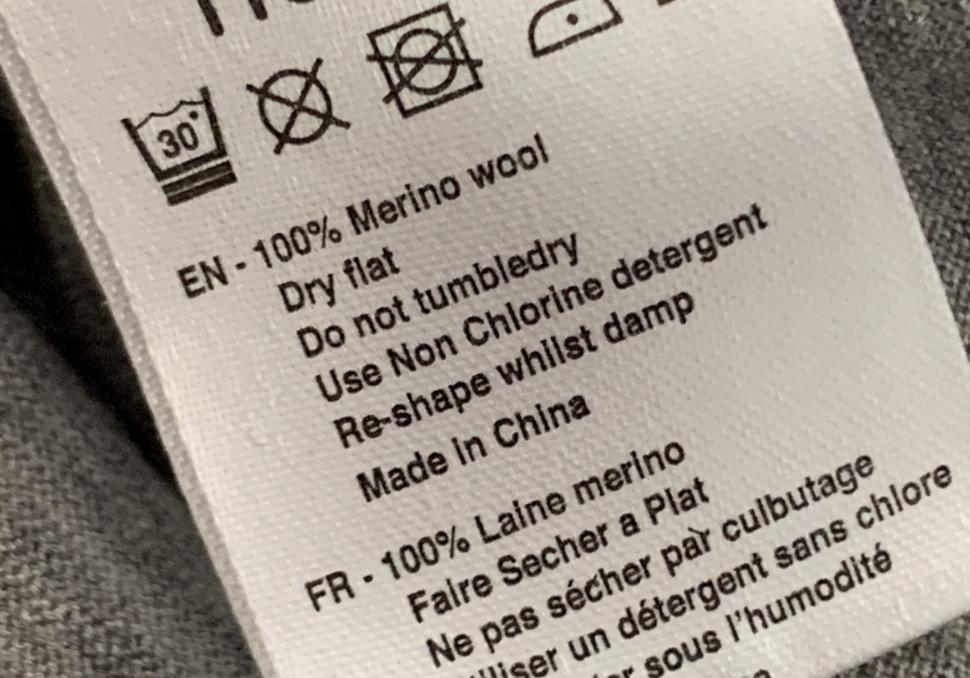

Don’t discount Merino!

One area where cycle clothing brands – and British manufacturers in particular – have long been involved with sustainability is merino wool.

This highly sought-after fabric is ecologically grown as fleece from merino sheep, whose only ‘fuel’ is water and grass. Yet its technical properties, especially in terms of heat retention and breathability, are a match for any man-made material.

It’s also incredibly soft and its natural oils are anti-bacterial, so it doesn’t get smelly as quickly and therefore requires fewer washes. Which means by wearing merino you’re helping to save the planet by using less water, electricity and cleaning products, too!

Latest Comments

- Webstaff 1 hour 14 min ago

Those same car are also likely to have auto stop....

- Webstaff 1 hour 30 min ago

Also we only get one side of the story when it's social media....

- No Skinny Tyres 2 hours 1 min ago

It's a stabiliser, it was first used in WW2 to preserve chocolate in US rations. It allows the milk solids to fully dissolve, US chocolate is less...

- Rome73 2 hours 16 min ago

LOL , me too the other day, I was on my GSD and got stuck behind a Cadillac Escalade (I think that is what they are called). It was so fat and over...

- eburtthebike 10 hours 48 min ago

The deterrent effect is almost certainly due to the massively increased likelihood of the offence being detected. As with other crimes, if the...

- Martin1857 11 hours 15 min ago

As a member of the Co-op community (I live in a Housing Co-op) and a bike owner /rider, this is very sad news. We need more Co-ops not less.

- Dnnnnnn 11 hours 6 min ago

It is sad for the individuals concerned but (and this is a general point, rather than specific to this story), we're much better off overall for...

- No Reply 11 hours 57 min ago

I agree with Pogacar regarding social media. The likes of Facebook, Instagram have done untold damage, especially to the minds of young people....

- David9694 12 hours 2 min ago

Lorry carrying 25 tonnes of beer catches fire on the M11...

- ktache 13 hours 7 min ago

That looks like a fun bike. Frame only, 2 and an 1/2 grand.

Add new comment

7 comments

And how much methane are those sheep contributing to warming the atmosphere !

Recycled 'ocean waste' sounds great on the tag, but surely it would be better to recycle those items before they ever end up in the ocean?

It probably would have been but I think that horse has bolted. It would be great to think that less plastic will be dumped in the sea in future.

The horse has already bolted for what's already there, but the best way to start tackling the problem is to reduce what's going in. If your sink is overflowing, you don't start by trying to plunge it or bail it out - you start by turning the taps off.

Focusing on recycling 'ocean waste' does nothing to incentivise the reduction of pollution of the ocean in the first place - it would be better to focus on recycling those sources of material that's otherwise going into the ocean.

Committing to wearing your gear many times us a good thing. Also consider washing in a guppy friend to stop all those recycled ocean plastics going straight back into the Atlantic!

Thanks for the suggestion, I hadn't heard of these. I just ordered one, hopefully it will do some good.

Is organic cotton really that environmentally friendly, as I understand it, production requires huge amounts of water.

My cycle wear, (and indeed much of the clothing I buy), gets used until it is properly dead. I still have jerseys that I must have brought 20 years back, that still are worn. Less every single day now, as when I add to the wardrobe, things become more specific, so more winter for the long sleves as I have brighter, lighter clothing for the warmer months and autumn for the short sleeved ones, as I have brighter for the summer and merino for full winter.

Fast fashion it is definitely not.

My casual off bike t shirts once unwearable through wear and holes become chain cleaning rags in their last dedeicated service to me.