- News

- Reviews

- Bikes

- Components

- Bar tape & grips

- Bottom brackets

- Brake & gear cables

- Brake & STI levers

- Brake pads & spares

- Brakes

- Cassettes & freewheels

- Chains

- Chainsets & chainrings

- Derailleurs - front

- Derailleurs - rear

- Forks

- Gear levers & shifters

- Groupsets

- Handlebars & extensions

- Headsets

- Hubs

- Inner tubes

- Pedals

- Quick releases & skewers

- Saddles

- Seatposts

- Stems

- Wheels

- Tyres

- Tubeless valves

- Accessories

- Accessories - misc

- Computer mounts

- Bags

- Bar ends

- Bike bags & cases

- Bottle cages

- Bottles

- Cameras

- Car racks

- Child seats

- Computers

- Glasses

- GPS units

- Helmets

- Lights - front

- Lights - rear

- Lights - sets

- Locks

- Mirrors

- Mudguards

- Racks

- Pumps & CO2 inflators

- Puncture kits

- Reflectives

- Smart watches

- Stands and racks

- Trailers

- Clothing

- Health, fitness and nutrition

- Tools and workshop

- Miscellaneous

- Buyers Guides

- Features

- Forum

- Recommends

- Podcast

feature

Puy de Dôme

Puy de DômeTour de France legends: The iconic Puy de Dôme returns to the Tour after 35 years

One of cycling’s dormant legends, the Puy de Dôme, will explode back into life on stage nine of the 2023 Tour de France. But why does this mythical dome-shaped volcanic plug in the Massif Central hold such an important place in the Tour’s history, despite not being used for 35 years? And what does its return say about the race itself, and its constant and complex fascination with modernity and tradition, innovation and nostalgia?

Ask any pro cycling fan to name the most romantic, emblematic Tour de France climb, and you’ll get a dozen or so different answers and opinions. Most of which will be wrong.

It’s not Alpe d’Huez, the ‘Wembley of cycling’, a climb so gainfully employed by the Tour since the 1970s that it became almost too familiar, to the extent that race organisers ASO have reduced it to a freelance role in recent years. What about the doyennes of the Alps and Pyrenees, the Galibier and the Tourmalet? Nah. Mont Ventoux is certainly in with a shout, its occasional use and aura allowing it to retain an inherent sense of mystique and drama.

But for anyone in their 30s or younger, the Puy de Dôme – an asymmetric green lava dome that towers over Clermont Ferrand and the Auvergne in central France – represents a mothballed snapshot of a bygone era of professional cycling and the Tour de France, a romanticised moment (imagined or otherwise) of the sport captured in time, before EPO, Lance, and the Sky train.

(A.S.O./Morgan Bove)

The Puy is an atmospheric, evocative climb, unlike any other used by the Tour. Unlike the hairpin bends of the Alps, its road, which only replaced the original railway in 1926, spirals like a corkscrew around the mountain in one relentlessly steep gradient to the summit. There you’ll find the mountain’s emblematic observatory tower, a second-century temple, and stunning views of Clermont Ferrand and the Chaîne des Puys, a chain of cinder cones and lava domes stretching for 25 miles across the Massif Central.

Thanks to its central location and ability to shake up a race due to its fearsome gradients, the Puy de Dôme became a regular feature on the Tour route following its first inclusion in 1952. By the time of its until-now final appearance in 1988, it held the joint record – along with Alpe d’Huez – as the most often used summit finish in the Tour’s history, featuring 13 times.

Myth Making

During that period, it played host to some of the race’s most symbolic, transcendental events, from Fausto Coppi’s win on the climb’s debut in 1952 to Bernard Hinault’s first authoritative stamp on the Tour in 1978 (and, incidentally, the Badger’s final concession to teammate and heir apparent Greg LeMond in 1986).

The Puy was also the scene of the beginning of the end of one of cycling’s defining eras. In 1975, Eddy Merckx, aiming for his sixth Tour win and momentarily succeeding in keeping Lucien Van Impe and home favourite Bernard Thévenet within arm’s reach on the summit finish, was punched in the kidneys by spectator Nello Breton. Injured from the impact of Breton’s ‘accidental’ intervention, the Cannibal’s reign at the top of his sport would end in Pra-Loup two days later.

However, there is one day, and two racers, that encapsulate the Puy de Dôme’s lofty standing in the Tour’s mythology more than any others.

In 1964 Maître Jacques Anquetil was four Tours to the good, an imperious, undroppable, but not extremely popular presence at his home race. Meanwhile, the younger Raymond Poulidor, who finished third overall two years previously, had emerged as his closest rival for the yellow jersey, and the true owner of the French public’s affections.

By the final mountain stage of the 1964 race, to the summit of the Puy, the two Frenchman – representing to fans the polar extremes of a cyclist’s character: one a relentless winning machine, the other a charismatic underdog – were separated by only 56 seconds on the GC.

While Julio Jiménez and Federico Bahamontès tore off up the ever-steepening road to the top of the volcano, the stage win and mountain points in mind, Poulidor and Anquetil remained locked together behind, literally shoulder to shoulder, matching each other pedal stroke for pedal stroke.

Was Anquetil bluffing, riding alongside his rival in an attempt to conceal his discomfort and to dissuade the overly cautious Poulidor from attacking? We’ll never know, but when Poulidor finally unleashed his killer blow – within sight of the summit – he put 42 seconds into the battling, for once ragged Anquetil in under a kilometre.

Despite the pyrotechnics, it was all too little, too late: the defending champion remained in yellow – by 14 seconds. “That’s 13 more than I need,” he said at the finish. As Maître Jacques slumped exhausted onto the bonnet of his team manager’s car at the top of the volcano, the myth of Anquetil and Poulidor’s rivalry – and of the Puy de Dôme – was born.

However, all good things must come to an end, and for three and a half decades anyway, the relentless march of modernity, and practical necessity, superseded the Tour’s penchant for unabashed nostalgia.

By the late 1980s, the continued expansion of the Tour into a global behemoth, with its cavalcade of vehicles and infrastructure, had made hosting the race on the Puy de Dôme’s cramped summit a logistical nightmare, a difficulty only enhanced by the construction of a funicular railway to the summit in 2012, further shrinking the already narrow road and reducing its status as a cyclo-tourist destination to one predetermined day a year.

While it was still used by adventure races such as the Transcontinental, where it hosted the 2017 edition’s first checkpoints, the Puy’s days as a Tour summit finish were thought to be long gone.

Past and Present

View from the top (A.S.O./Morgan Bove)

However, as the volcano’s mythical status grew in the years since its last appearance in 1988, so too did the clamour for its return. According to Tour director Christian Prudhomme, bringing the Tour back to the Puy de Dôme was the first objective he set himself when he joined ASO back in 2004.

Successful experiments at smaller-scale summit finish operations, such as those on the Galibier and Tourmalet, as well as the Super Planche des Belles Filles, showed Prudhomme that his goal was at least possible, and whispers of a return to the Puy duly intensified by the early 2020s. Those rumours were finally confirmed last October, when the Tour director confirmed that, after 35 long years, the Puy de Dôme would host the summit finish of stage nine of the 2023 Tour.

While it’s all well and good waxing lyrical about mythical battles of a bygone era – a facet of the Tour’s identity at which Prudhomme has certainly excelled as director – what should we expect when it comes to the racing in 2023?

UAE Team Emirates tackle the Puy de Dôme during a pre-Tour recce (A.S.O./Morgan Bove)

Well, first of all, don’t be expecting Mathieu van der Poel to emulate his grandfather – whose hometown of Saint-Léonard- de-Noblat will incidentally host the stage start – on the volcano’s fearsome slopes (though you never know with the mercurial Alpecin-Deceuninck star).

Because the Puy de Dôme is a relentless monster of a climb.

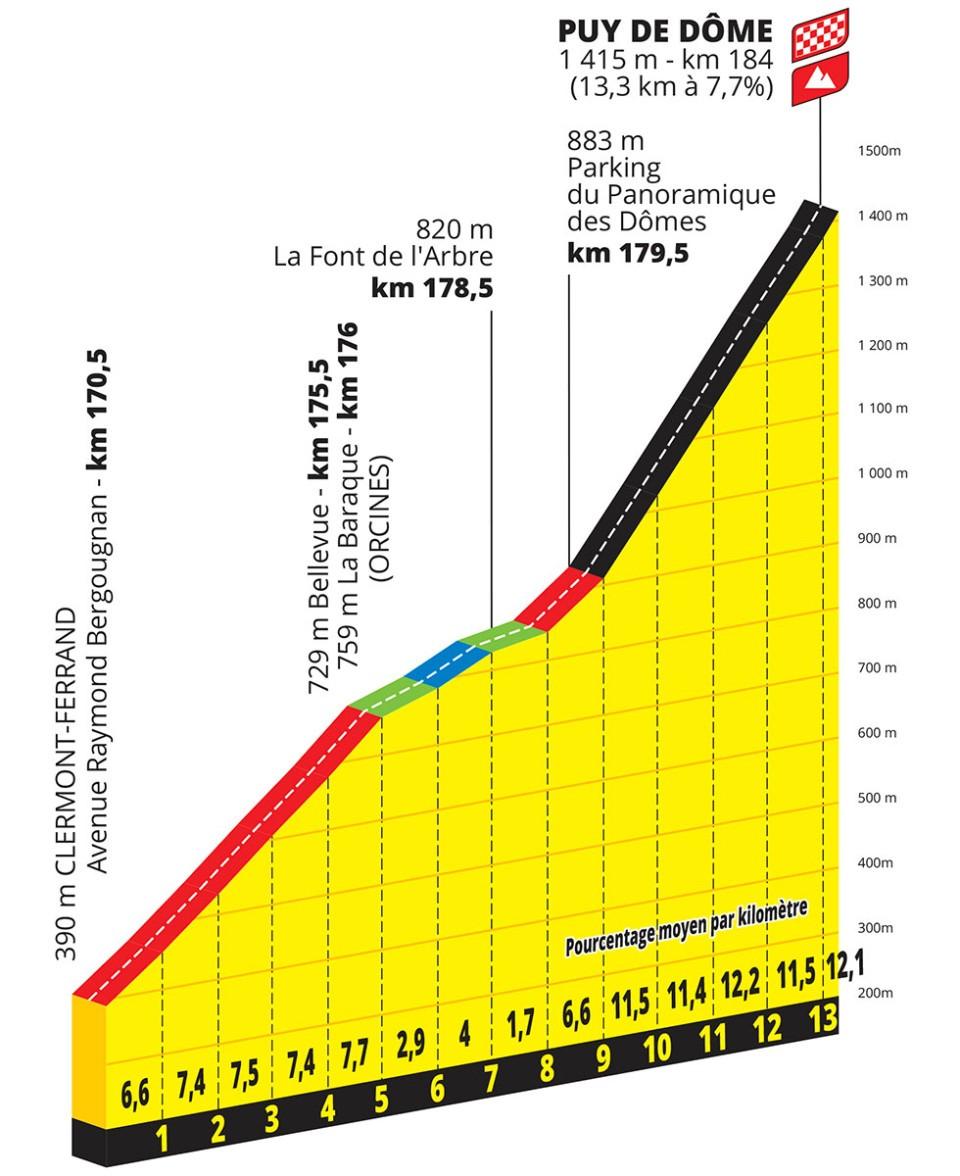

Rising sharply out of Clermont-Ferrand, the road then eases off for three kilometres of relative false flat before stage nine’s defining moment on the dome, where a still sizeable group could be spat out onto the extremely narrow and steep road to the summit – three riders wide, tops – and left to fend for themselves.

The final four kilometres are, it’s safe to say, savage. According to VeloViewer, the unrelenting gradient never dips below 11.5 percent, and touches 18 percent in the final 200m, with not a bend or hairpin in sight to ease the suffering.

Due to the narrowness of the road, and the mountain’s status as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, with its focus on preserving the local flora and fauna, no spectators will be allowed in the final four kilometres. The lack of fans (300,000 were estimated to be on the Puy to watch a time trial at the 1983 Tour) will do little to dampen the spectacle, however.

Egan Bernal tests his legs on the Puy earlier this year (A.S.O./Morgan Bove)

It may not be the longest climb, but it will certainly do some damage, and will likely favour a climber capable of withstanding steep gradients while retaining some sort of kick at the end. It seems tailor-made for Tadej Pogačar then, though perhaps local boy Romain Bardet could spring a surprise and take a popular home victory?

If Bardet, from nearby Brioude, is to triumph on the Puy, he’ll have to channel the spirit of the ancient Averni, who defeated the Roman Republican army led by Julius Caesar at the Battle of Gergovia, held in the shadow of the Puy de Dôme, in 52BC.

Despite the Averni’s victory – forged on the basis of an intelligent counterattack (take note Romain) – the Romans’ overwhelming strength ensured that they ultimately prevailed in the region, a fate that may await any GC contender foolish enough to attempt to unsettle the might of Jumbo-Visma and UAE Team Emirates on the Puy.

“It’s a different climb to those we usually tackle,” Bardet said before the Tour. “The road surface is perfect and winds around the mountain at a steep but steady gradient. I won’t be at all surprised to see the future Tour de France winner prevail at the top of the Puy de Dôme.”

Will 2022 Tour winner Jonas Vingegaard still be up for sampling the view after stage nine? (A.S.O./Morgan Bove)

In any case, whoever makes it to the top first may be inclined to offer up a prayer at the Temple of Mercury, a second-century place of worship which lay undiscovered for centuries, until it was unearthed during the construction of the mountain’s first observatory in the 1870s.

Just like that nineteenth-century discovery, the unearthing of the Puy de Dôme as an iconic Tour de France venue on Sunday will once again underline both the mountain and the race’s ever-evolving, ever-complex relationship with tradition and innovation, and its storied past and exciting present.

And the peloton of 2023 will finally – after 35 long years – be able to add another layer to the story of the Puy de Dôme.

After obtaining a PhD, lecturing, and hosting a history podcast at Queen’s University Belfast, Ryan joined road.cc in December 2021 and since then has kept the site’s readers and listeners informed and enthralled (well at least occasionally) on news, the live blog, and the road.cc Podcast. After boarding a wrong bus at the world championships and ruining a good pair of jeans at the cyclocross, he now serves as road.cc’s senior news writer. Before his foray into cycling journalism, he wallowed in the equally pitiless world of academia, where he wrote a book about Victorian politics and droned on about cycling and bikes to classes of bored students (while taking every chance he could get to talk about cycling in print or on the radio). He can be found riding his bike very slowly around the narrow, scenic country lanes of Co. Down.

Latest Comments

- Born_peddling 4 hours 3 min ago

Muddyfox tour 100's I've wide & flat feet plus there's the optional choice of using cleats with them...

- Prosper0 3 hours 58 min ago

Just doing the Lord's work in case anyone's interested in this product. This Mucoff Pump is a £100 rebrand of an £85 Rockbros rebrand of a £60...

- mdavidford 4 hours 42 min ago

You forgot ignoring half the race to show awkward interviews with the riders' Proud Parents™ instead.

- mdavidford 4 hours 46 min ago

Obviously it means 'springing out of the bunch' on a critical sector. Or maybe it's referring to the time of year.

- David9694 5 hours 33 min ago

Car crashes through garden wall for second time in 18 months https://www.wiltshire999s.co.uk/car-crashes-garden-second-time/

- David9694 5 hours 35 min ago

Woman taken to hospital after flipping car onto roof in Trowbridge...

- A V Lowe 6 hours 17 min ago

Its blindingly obvious from the image that the DKE of the buses include the mirrors which extend to nearly reach the edge of the tarmac pavement on...

- Sredlums 6 hours 50 min ago

It's sad when being very good at your job - any job - isn't enough to earn a decent living. It shouldn't be that way....

Add new comment

1 comments

Alp D'Huez the wembley of cycling !